OK, if you are reading this, then you, like me, are probably a Map Addict to some extent or another. As with any obsession/compulsion, map addiction takes many forms and there are many degrees of addiction. And there are no 12-step programs to cure people of map addiction, because, well, quite frankly, we don’t want to be cured!

I have just finished reading

Map Addict, by Mike Parker, which was recommended to me by Gretchen Culp before I left for England. She thought I would enjoy it because 1.) I am a map addict; 2.) she enjoyed the book (and is also a map addict); and 3.) it pertains largely to England and Wales and the U.K. Ordnance Survey (OS) maps, and I was just heading off to England. I found out about this book too late to include it in my list of “Geography Beach Books” for summer reading, which I posted back in May of this year (see

http://geographer-at-large.blogspot.com/2011/05/geography-beach-books.html) so I would like to amend the list by saying it is definitely worthy of being added. Since I just returned from England (and from reading this book), I thought it was fitting to provide a little review of it. The little review then blossomed into an all-out mini-dissertation on the book. In the style of the book’s author, one thing led to another as I was writing this review, and before you know it, I was off on a zillion tangential digressions. That’s the way it is with maps – somehow they inspire a fascination with, well, nearly EVERYTHING, exploring all possible paths and going down seemingly unrelated avenues and blind alleys, regardless of how far afield they may take us from the original route of the journey. THAT is one of the joys of map addiction – endless hours spent poring over maps, even if the map is of a place where you have very little likelihood of ever going in real life.

Mike Parker, a self-professed map addict, writes in an engaging and informal style, detailing his life’s obsession with maps in terms that most of us who also fall into the map addict category can certainly relate to. I definitely count myself in that group, and I suspect that many of you who are reading this do, as well. Throughout the book, he discusses many of the fascinating aspects of maps, from the perspectives of politics, gender, and religion, among other connections. Much of this is told with a decidedly British focus, as filtered through the lens of someone who grew up in a certain place in a certain time. Nevertheless, even for a non-Anglophile, it is quite interesting and even at times illuminating.

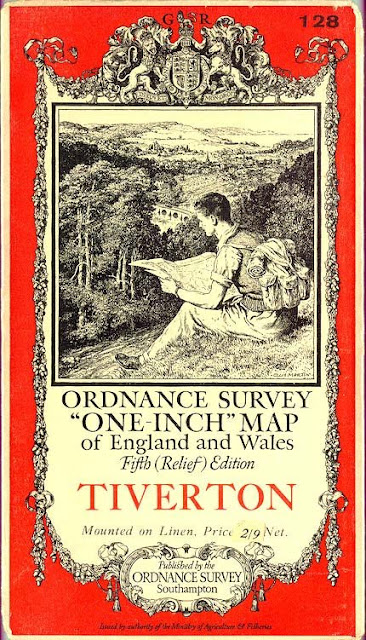

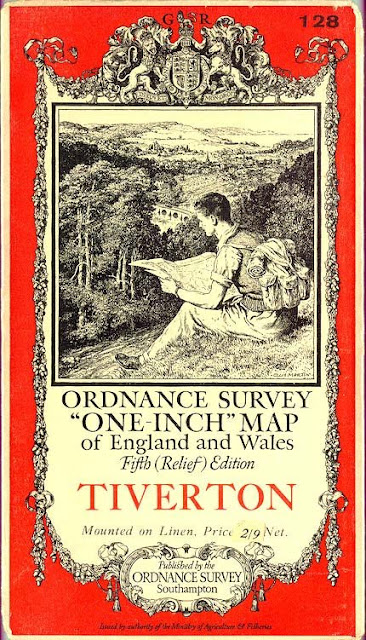

The author starts by describing the origins of his map obsession, which began for him as a child who had discovered and fallen in love with the British Ordnance Survey maps. His raptures about these maps may not be well-understood right away by those readers who have not had a first-hand experience with the OS maps themselves, but Mike does a good job of explaining what makes these maps so wonderful and special. They are not only extremely detailed - in the larger scales showing every little farmstead and outbuilding and country lane - but are also aesthetically beautiful and models of clarity and good cartographic design. Their color and symbolization schemes are amongst the best ever invented. He talks about the history of the Ordnance Survey itself, going back to the 18th century, the major personalities involved in the initial Survey, and all the trials and tribulations of getting the Survey accomplished, from the technical as well as the political standpoints. Interspersed throughout the more factual aspects of the account are the author’s personal ruminations about mapping and the love of maps, which I found generally delightful, not the least of which because I happen to agree with most of them!

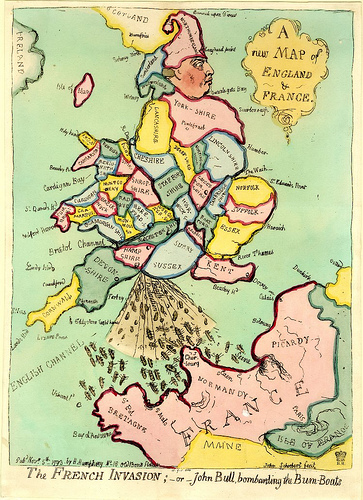

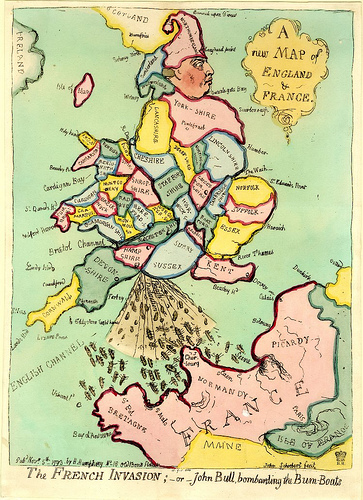

“James Gillray’s map of England as King George III, crapping ‘bum boats’ into France’s mouth”

The second chapter deals with the national rivalry between France and England in all things, not the least of which is cartography, owing to its ramifications for national security and military operations of these two historic “frenemies” who face each other across this narrow body of water (the countries are only 21 miles apart at its narrowest point) called alternatively the English Channel in the U.K., or la Manche in France. Therefore cartography and having the most up-to-date spatial information about coastlines, etc. has played a large role over the centuries in both English and French politics. Mike regales us with the very convoluted and somewhat humorous (at least to the victors!) tale of the international commission that ultimately established Greenwich, England as the location of the Prime Meridian - this despite the valiant efforts of the French representative to locate it in Paris. This was the culmination of a long-standing feud about the standardization of Longitude 0o 00’ 00” and although many countries had their own Prime Meridian in use for navigation, only England and France, for various reasons, had any “real” and legitimate claim to having their locations recognized and used internationally.

Cover of an Ordnance Survey Map, 1 inch to the mile series, from 1889.

The third chapter reverts back to a more in-depth look at the Ordnance Survey maps, and Mike selected (given with painstaking rationales) his top five OS maps, and more entertainingly, his pick of the worst five. I have had the utmost respect for and admiration of the OS maps over the years, but this chapter really did open my eyes as to why the Ordnance Survey is unique in the world of national mapping agencies and their products, and permitted a level of appreciation of these maps that heretofore was more intuitive on my part rather than based on objective measures. He also goes into all the different series of maps available over the years, in the different scales, and the advantages and disadvantages of each, as well as an analysis of the cover designs of the maps, and a history of changes to the design and perceived purpose of the maps.

Enclave/Exclave of Madha and Nahwa. Source: Wikipedia entries for Madha and Nahwa.

I found Chapter Four, “Borderline Obsession,” extremely fascinating – it’s about borders, enclaves and exclaves. An enclave is a territory (or part of one) completely surrounded by another territory. Usually (but not always) an enclave is also an exclave (i.e. a part of a territory not connected to its ‘mainland’), so both terms are often used interchangeably. This chapter reminded me in parts of a section of the Frank Jacobs’ book

Strange Maps: An Atlas of Cartographic Curiosities, that deals with the same topic. Also, see Frank’s website for another discussion about the strange phenomena of exclaves and enclaves. He has several posts on the topic of exclaves/enclaves, here are a couple of the best ones:

http://bigthink.com/ideas/21160 (“Cooch Behar, the Mother of all Enclave Complexes,” on the India-Bangladeshi border);

http://bigthink.com/ideas/21109 (on Madha and Nahwa on the Arabian peninsula);

http://bigthink.com/ideas/24238 (Switzerland/Italy). Another blogger who has taken up the topic of exclaves/enclaves and borders in general is the Basement Geographer, in posts such as “The Legacy Enclaves of Portuguese and French India,” at

http://basementgeographer.blogspot.com/2011/06/legacy-enclaves-of-portuguese-and.html (one of which is Pondicherry, where one of my top viewers is located!).

This chapter on borders also expounds upon what has happened in England throughout the past decades in revising county names and county borders and the impact on issues of civic pride, heritage, and nostalgia for times past. He does a very good job of framing many of the pressing problems of the current day in terms of place/space, and of course, maps.

“The Power Map,” Chapter 5, is a really nice synopsis and expansion of many of the ideas popularized by geographers such as Mark Monmonier, Danny Dorling, Denis Wood, and others in various books about the “power of maps” – how maps have been used throughout the centuries to achieve political ends, to promote propaganda, and in general to influence ways of thinking about our world. Mike Parker explains how no map is truly objective or totally factual, and how every map distorts. He talks about what is included and what is left out of maps (and why), as well as reviews the whole map projection controversy, which for a time was a vehement debate between supporters of equal area projections such as the Gall-Peters projection, vs. the traditional Mercator projection, which ostensibly promotes a Euro-centric, Imperialist, “northern” superiority. (For a humorous look at this, see my recent posting on “Freeing the Prisoners of the Mercator Projection” at

http://geographer-at-large.blogspot.com/2011/06/freeing-prisoners-of-mercator.html) . The issue of the subjectivity of north being “on top” is also discussed in terms of the greater political and psychological ramifications, and how worked up people can get about changes to the traditional way of mapping the world. It is very disturbing! It can put people into a tailspin and it turns their worldview upside-down!

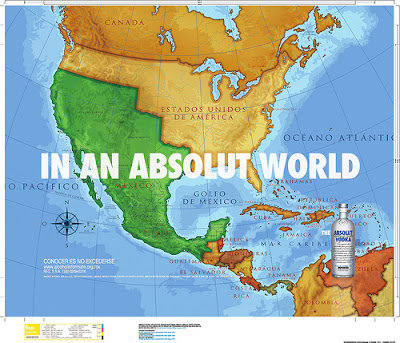

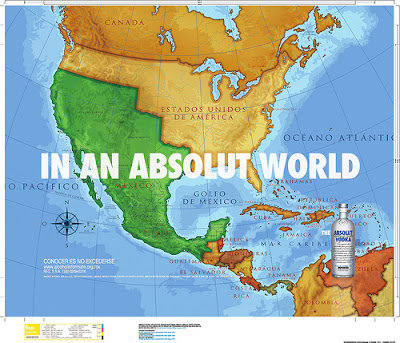

“The controversial Absolute vodka ad, showing Mexico in its pre-1848 borders”

Changes to the standard map can be hazardous to a fragile or insecure self-image, as with what happened when Absolut Vodka had an advertising campaign that featured a map of the U.S. and Mexico that depicted the borders of Mexico as including all its former possessions in California, Texas, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico and parts of Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming, before it lost those territories to the U.S. in 1848 in the aftermath of the US-Mexican War. Some Americans got very riled up by this, and flushed their Absolut Vodka down the toilet. The ad was such an affront! You can read some of the outraged comments on the website where Absolute Vodka’s “apology” or explanation or whatever is posted. Some very interesting points are raised about what constitutes an “ideal view of a country.”

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1996876/posts

Absolut’s explanation: “We have received many comments on an ad showing what an ABSOLUT [i.e., a perfect] world would look like from a Mexican point of view......The In An Absolut World advertising campaign invites consumers to visualize a world that appeals to them -- one they feel may be more idealized or one that may be a bit ‘fantastic.’… This particular ad, which ran in Mexico, was based upon historical perspectives and was created with a Mexican sensibility. In no way was this meant to offend or disparage, nor does it advocate an altering of borders, nor does it lend support to any anti-American sentiment, nor does it reflect immigration issues. Instead, it hearkens to a time which the population of Mexico may feel was more ideal.”

Most of the responses were knee-jerk “patriotic” ones of the Absolut-boycotting and flushing-down- the-toilet variety, but here are some of the more thoughtful responses/critiques of their explanation:

“It's a good thing that Muslims don't drink alcohol, because in an Absolut world, would Israel not exist?” and

“So I assume the ad in Japan will show a Greater East Asia co-Prosperity Sphere?” and

“Imagine if your ad company created an ad for the German market that showed a map of Europe during WWII that had all the land that Hitler overtook- including Sweden, with the caption- In An Absolut World. How do you think the folks in Sweden would take that?” and

“Did you know at one point in Medieval Europe there were over 100 countries, maybe more? I guess we should start a campaign to bring back all the lost worlds, and reorganize all the borders for them. Should we bring back Rome and Carthage? Or how about the kingdom of Burgundy? Maybe we should restore the Ottoman empire, or the Mongol empire. Better yet, let's bring back the Sumerians. It's really annoying how people use that map as an argument of manifest destiny…” and

“It could be worse: you could have been French”

And, the last word!

“I think in an absolute world there would be no borders, we'd all be drinking tequila and beer, and there would be tamales and beans and rice for all.” My sentiments, exactly!

And, as usual, Frank Jacobs picked up on this particular story as it unfolded back in 2008 in his blog

Strange Maps at http://bigthink.com/ideas/21316.

Map Addict makes the point that the Absolut map harkens back to the 18th and 19th century caricature maps popular with satirists and were well-known as parodies (something their 21st century counterparts seem to have no understanding of, and no sense of humor about, either!). I recently wrote several posts on these political/satirical maps, see

http://geographer-at-large.blogspot.com/2011/06/anthropomorphic-and-zoomorphic.html OK, back to Map Addict. Chapter 6, “God is in the Detail,” explores the topic of maps as symbolic representation of spiritual/religious concepts, such as the T-in-O maps and mappae mundi from mediaeval times. The chapter covers many things. One of the delightful aspects of this book in general is that Mike Parker rambles and segues from one topic to the next, seemingly unrelated, topic, and then brings it all back together at the end, and in the process introduces many esoteric facts and interesting contemplations. For instance, this chapter starts off with some rather profound observations: “Man’s eternal need to define God has meant that the Almighty has had almost as big an influence on the history of mapping as that other great human impetus, war. The two are, of course, indissolubly linked. Maps are used to demonstrate God, in an attempt to quantify and codify the divine, but they can also encourage us to stray into the territory of acting like tin gods ourselves. There is something superhuman in the unfurling of a map, a feeling that you are, in some small way, lord and master of all you survey.”

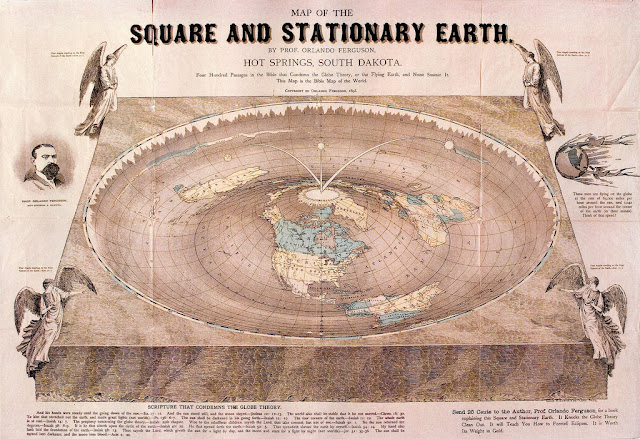

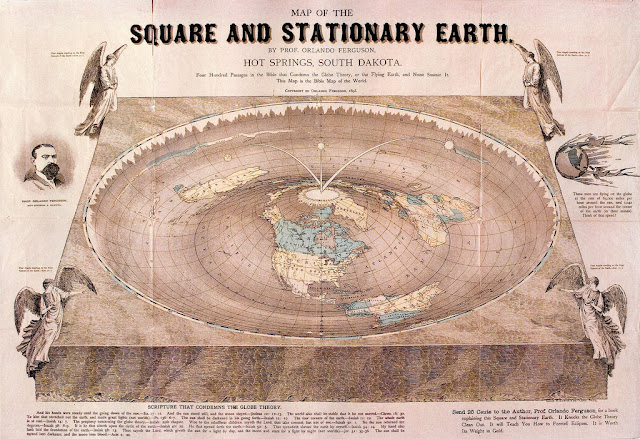

He then moves on to discuss the Tesco-ing of Britain (Tesco is the ubiquitous supermarket chain), Lewis Carroll’s last novel in 1889 that includes a bit about a map that is at a scale of one mile to the mile, to the Jorge Luis Borges story “On Exactitude in Science” about the same conceit of a 1:1 map and the consequent death of geography, back to how religious fervor changed cartography (and geographic knowledge) in Europe for nearly 1,000 years, with some major back-sliding from Ptolemy’s depiction of the earth as a sphere to the Christian zealots’ vision of a flat- and square-earth with four corners, mimicking the design of the tabernacle described in St. Paul’s Letter to the Hebrews, with the heavens forming a curved ceiling above. The maps produced during this period are less about the reality of the earth, and more about promoting a Christian sensibility and worldview, with Jerusalem in the center of the map, east (the location of Paradise) at the top, and little regard for exact placement of the continents or anything else. In the sixth century, Cosmas Indicopluestes of Alexandria, a well-traveled sailor whose name means “traveled to India,” converted to Christianity and became one of the fiercest opponents of the idea of the spherical earth and the rotation of the earth and the stars. “Here then the Pagans are at war with divine Scripture; but, not content with this, they are at war with common sense itself and the very laws of nature, declaring, as they do, that the earth is a central sphere, and that there are Antipodes, who must be standing head-downward and on whom the rain must fall up.” These attitudes and beliefs gave rise to subsequent maps showing strange creatures living in the unknown parts of the world, with feet on top of their heads like giant umbrellas, and other strange beings living in an upside-down world. Believers in a fourth continent (the Antipodes) were branded as heretics. Almost unbelievably, this flat earth belief did not die hundreds of years ago, but still persists, as evidenced by the recently re-discovered tract about the square and concave world.

The Bible Map of the World, 1893, by “Professor” Orlando Ferguson of Hot Springs, South Dakota, a geocentrist who created the map based on 400 passages in the Bible that supposedly describe what the Earth is like, and none of them supports the idea of a spherical earth, or one that revolves around the Sun. Apparently, according to a 1996 Gallup poll, about 18% of Americans agree and believe the Sun revolves around the Earth.

Map Addict then segues into the unfortunate saga of one of the most famous of all the mappae mundi, the Hereford map, which was to have been put on the block at Sotheby’s auction house by the Hereford Cathedral when they were strapped for operating funds back in the 1980’s. This story transitions into a history of the Hereford mappa mundi, then on to John Ogilby’s 1675 Britannia “road atlas,” which he shows might have had an elaborate hidden subtext of support for Catholicism at a time when Catholics were under siege in Britain, and finally bringing in ex-Monty Python Terry Jones’ Great Map Mystery, a Welsh TV series that, in one episode, presented some interesting theory that the Britannia map was actually a cartographic blueprint for a French (Catholic) invasion of (Protestant) England and Wales.

Next, Map Addict tackles the pagan aspects of the landscape and mapping by tracing sacred alignments, leylines, and features throughout the British Isles, which exist even in a “New Town” purpose-built in the 1960’s. All this results in fascinating reading, and the feeling that you are getting the benefit of a long conversation with someone very knowledgeable about many, many things, and someone who can bring almost any topic around to his love of maps.

Chapter 7, “Carto Erotica,” continues the theme of pagan landscapes by delving into the mysteries of some of the giant erotic earthworks in Britain, such as the Cerne Giant, outlined in chalk, with his 30-foot long penis, created perhaps in Bronze Age times, around 1,400 BC, like the other chalk-hill figures in Britain which have been carbon-dated, but no one is really sure how old the Giant is. To add to the mystery, the only way to really perceive what the figure is, you need a view from above, something possible only within the past century. There are also the female equivalents, the recumbent goddesses, such as the Sleeping Beauty in the Outer Hebrides. Exactly why these types of figures were created, and with great effort in the days before earth-moving machinery, is still unknown. This leads nicely into a catalogue of many erotic place names, and how people back in the day named things unsqueamishly and honestly to reflect their actual purpose. No beating around the bush here, as it were. Before street maps were in common usage, people had to rely upon street names giving clues about the lay of the land. This resulted in a quite literal nomenclature, such as Church Street, School Road, Tanners Row, Smith Lane, etc. Every town had some version of a red-light district, amenable to prostitution and other vices. Often these streets were picturesquely called “Gropecunt Lane.” Many of these were renamed in more prudish times as “Grope Lane,” or “Grove Lane,” obscuring their original raison d’etre. There were also streets called Hookers Court, Dunghill Lane, Pissing Alley, and Maiden Lane, a more euphemistic and “polite” title for a street providing the same services as in Gropecunte Lane.

After the sexy map talk, it is only natural to focus on the issue of gender and maps, and in particular the theory that women can’t read maps, and moreover, are not very interested in maps. Since this is along the same lines at the Royal Geographical Society’s pronouncement that women are incapable of being geographers, I read Chapter 8, “Boys’ Toys?” with interest and some annoyance, since I am apparently doing two things that women typically can’t do, which I find absurd. So does the author, and he points out all the fallacies and holes in the theory.

The penultimate chapter takes on modern technology, specifically satellite navigation systems (GPS) referred to as “satnav.” While neither Mike Parker nor I are Luddites, it was refreshing to find someone who shares my dislike of the current trend of over-reliance on GPS for wayfinding. Not only can it be dangerous (people ending up unexpectedly in rivers or on railroad tracks when their satnav systems erroneously direct them there), but it reduces peoples’ ability to appreciate the larger geography. After all, when using satnav, we only see one tiny and fragmented part of the landscape at a time, and never really understand how it fits into the larger whole. It removes geographic context, obfuscates distance, topography, topology, and history, and encourages even more geographic illiteracy amongst the populace, and that is definitely something we don’t need, based on the already abysmal understanding of basic geography demonstrated in many polls and surveys. He also decries the use of Google “mash-ups,” while extolling the virtues of Internet map libraries and “good” uses of GIS, acknowledging that GIS has revolutionized geography in schools. He’s enough of a die-hard paper map enthusiast, however, to believe that there will always be a need for paper maps, and that the digital turn in cartography will never totally replace “real” tangible maps.

Throughout the book, Mike intersperses his personal recollections, observations, and ruminations of things geographical into the factual narrative. The final chapter is the culmination of the personal aspects of the book, where he questions whether or not all this map-reading has reduced his enjoyment of traveling and experiencing life “in-the-moment.” He wonders if having his head stuck in a map all the time has diminished his noticing important things in real life, and skewed his view of reality. In other words, was he too much of a map addict for his own good? He questioned whether “years of over-reliance on maps have dulled any innate sense of direction” after becoming hopelessly lost once when venturing out without a map in hand. But he concludes that while it is good for the soul to go “off-map” occasionally, “it doesn’t feel right; indeed, it feels as if I am denying myself one of the main joys of walking in the first place, namely to compare the route on the map with the reality around me.” Spoken as only a true map addict would.

Map Addict, by Mike Parker, 2010, Harper Collins Publishers, London, UK